<Counter-Reformation to 19th Century.

In the period of the Counter-Reformation, during the

reigns of Maximilian II (1564-76), *Rudolph II

(1576-1612), and Matthias (1612-19), there were frequent

expulsions and instances of oppression.

[Protected Jews under

Ferdinand II]

Under Rudolph the Jewish population in Vienna increased;

certain families enjoying special court privileges

("hofbefreite Juden") [["Jews liberated by the court"]]

moved there and were permitted to build a synagogue.

In 1621 *Ferdinand II allotted the Jews of Vienna a new

quarter outside the city walls. In the rural areas the

jurisdiction over the Jews and their exploitation for

fiscal purposes increasingly passed to the local

overlords. Important communities living under the

protection of the local lordships existed in villages

such as Achau, Bockfliess, Ebenfurth, Gobelsburg,

Grafenwoerth, Langenlois, Marchegg, *Spitz,

Tribuswinkel, and Zwoelfaxing.

In Vienna also, *Ferdinand III (1637-57) temporarily

transferred Jewish affairs to the municipality. The

*Chmielnicki massacres in Eastern Europe (1648-49)

brought many Jewish refugees to Austria, among them

important scholars.

[Expulsion of the Jews

from Vienna under Leopold I]

The situation of the Jews deteriorated under *Leopold I

(1657-1705). In 1669 a commission for Jewish affairs was

appointed, in which the expulsion of the Jews from

Vienna and the whole of Austria was urged by Bishop

Count *Kollonch. In the summer of that year, 1,600 Jews

from the (col. 890)

poorer and middle classes had to leave Vienna within two

weeks; and in 1670 the wealthy Jews followed. The edict

of expulsion remained nominally in force until 1848,

although sometimes transvened.

A number of *Court Jews in particular, such as Samuel

*Oppenheimer, Samson *Wertheimer, Simon Michael, and

Joseph von Geldern, were permitted to live in Vienna.

Their households included Jewish clerks and servants. In

1752 it is estimated that there were 452 Jews living in

Vienna, all of whom were connected with 12 tolerated

families.

[18th century until

1848: Discrimination of Jews by segregation, by

marriage laws - Turkish Jews since 1718]

Restrictive legislation was enforced in most localities

in the Hapsburg empire; often Jews were segregated from

Christians. In 1727, in order to limit the Jewish

population, the *Familiants laws were introduced,

allowing only the oldest son of a Jewish family to

marry. They remained in force until 1848. By the peace

treaty of Passarowitz between Austria and Turkey (1718),

Jews who were Turkish subjects were permitted to live

and trade freely in Austria. Their position was thus

more favorable than that of Jews who were Austrian

subjects. In 1736, Diego d'*Aguilar founded the "Turkish

community" in Vienna.

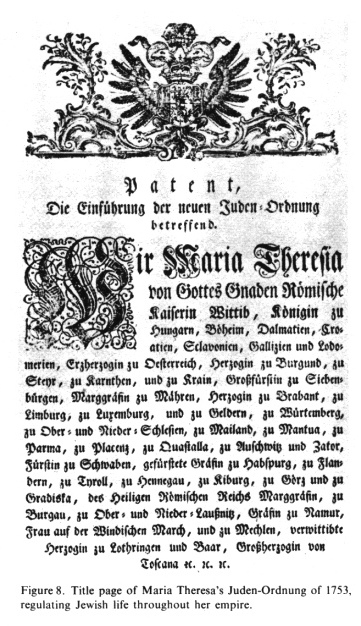

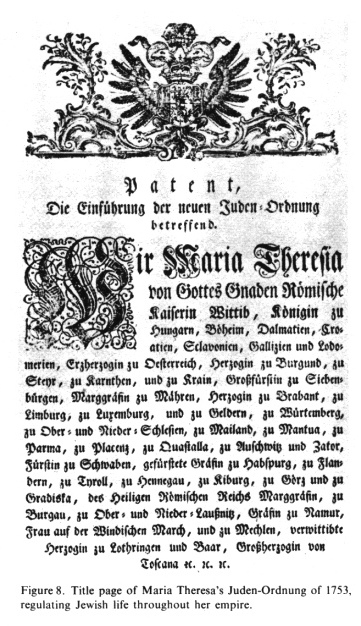

Jewish order of Maria

Theresa, 1753

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Austria, vol.3, col.903:

Jewish order 1753: Title page of Maria Theresa's

Jewish Order ("Judenordnung") of 1753, regulating

Jewish life throughout her empire. |

[Jews as "useful

citizens" under Joseph II]

From the end of the 18th century, with the growing

centralization of the government of the empire and new

political developments, the position of the Jews in

Austria proper became increasingly linked with the

history of the empire as a whole. As part of his

endeavors to modernize the empire, *Joseph II (1780-90)

attempted to make the Jews into useful citizens by

introducing reforms of their social mores and economic

practices and abolishing many of the measures regulating

their autonomy and separatism.

Although not altering the legal restrictions on Jewish

residence (mainly affecting Vienna) or marriage, he

abolished in 1781 the wearing of the yellow badge and

the poll tax hitherto levied on Jews.

[1782: The

Toleranzpatent - Jews between assimilation and

cultural identification]

Joseph II's Toleranzpatent

[[law of tolerance]], issued in 1782, in which he

summarized his previous proposals, is the first

enactment of its kind in Europe. Jews were directed to

establish German-language elementary schools for their

children, or if their number did not justify this, to

send them to general schools. Jews were encouraged to

engage in agriculture and ordered to discontinue the use

of Hebrew and Yiddish for commercial or public purposes.

It became official policy to facilitate Jewish contacts

with general culture in order to hasten assimilation.

Jews were permitted to engage in handicrafts and to

attend schools and universities. Jewish judicial

autonomy was abolished in 1784. Jews were also inducted

into the army, which in due course became one of the

careers where Jews in Austria enjoyed equal

opportunities, at least in the lower commissioned ranks.

The "tolerated" Jews in Vienna and the (col. 892)

intellectuals who, influenced by the enlightenment

movement (see *Haskalah), tended toward assimilation,

accepted the Toleranzpatent

enthusiastically. The majority, however, considered that

it endangered their culture and way of life without

giving them any real advantages. The implementation of

these measures promoted the assimilation of increasingly

broader social strata within Austrian Jewry. In 1792 the

Jewish Hospital was founded in Vienna, which benefited

Jews throughout the Empire for many years. In 1803,

there were 332 Jewish families living in Austria proper

(including Vienna), and approximately 87,000 families

throughout the Hapsburg Empire.> (col. 893)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

1971: Austria, vol. 3, col. 887-888

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

1971: Austria, vol. 3, col. 887-888